There just isn't enough aspirin in the world to get rid of this headache of mine. Another week of total brain damage...but I have a plan, and it is so "Crazy" it might just work...because "doing the right thing" in "good faith" doesn't compute with the Wonder that is JPMorgan Chase. **Stay Tuned**

***************************

Dimon's $23 million payday isn't the problem

updated 8:36 AM EDT, Fri May 18, 2012

A cutout figure of JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon hovers above a May 2011 protest against banks on Wall Street.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon gets $23 million pay package despite the bank's $2 billion loss

- Ingo Walter and Jennifer Carpenter: Real concern should not be level of executive pay

- They say bank shareholders and employees have incentives to take risks to make more money

- Focus on changing risk incentives rather than amount of pay, the writers say

Editor's note: Ingo

Walter is the Seymour Milstein professor of finance, corporate

governance and ethics, and Jennifer Carpenter is an associate professor

of finance in the Stern School of Business at New York University.

(CNN) -- Here we go again. The perennial question

of: "Would you rather own shares in a major financial conglomerate or

manage one?" comes up as JPMorgan Chase loses more than $2 billion in

trading bets.

The answer seems clear.

If you're an executive who manages the money, you're likely to get a

large paycheck and bonus even if you're responsible for the loss,

directly or indirectly. Jamie Dimon is still getting his $23 million.

Shares of the major banks

continue to trade well below book value and generate miserable

performance metrics -- and have over the years been very poor

investments -- while senior executives and key employees continue to

walk away with vastly outsize earnings, even when they oversee massive

losses.

Shareholders certainly

have reasons to object to huge executive pay packages, especially

ordinary people whose fund managers have put in stakes of the bank

shares in their pension and mutual fund accounts.

But the level of

executive compensation comes out of shareholders' pockets. If

shareholders are unhappy with the division of the spoils, they have no

one to blame but themselves. After all, they can always take their money

elsewhere if they don't think their cut of bank profits is big enough.

The real concern for

everyone -- including regulators and taxpayers -- is not the level of

pay handed out to executives, nor how profits in a company are divided

between employees and shareholders, but rather, the incentives for

risk-taking that bank pay apparently continues to create.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter and Facebook.com/cnnopinion.

Regulators have called

for deferred compensation to address the incentive problem. If deferred

compensation presents employees with serious exposure to potentially big

losses, they'll have a major stake in the long-term solvency of the

business and help spare taxpayers the cost of bailing out firms that

have become too systemically important to fail.

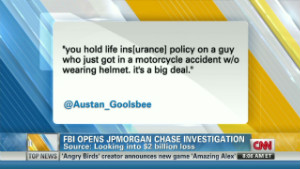

FBI looking into bank's huge loss

FBI looking into bank's huge loss

Professor: Fair to question Volcker Rule

Professor: Fair to question Volcker Rule

From AIG to JPMorgan, why London?

From AIG to JPMorgan, why London?

Carney: Well-run bank can make bad calls

Carney: Well-run bank can make bad calls

But forcing employees to

bear significant exposure to potentially big losses may come at a price.

Employees may require higher salaries to compensate for increased risk.

We're seeing this reflected in recently announced pay packages. The

price is paid primarily by shareholders while the benefits of any

improvement in financial stability accrue to society as a whole.

Deferred cash

compensation makes employees debt holders, so it ought to reduce

risk-taking. So should compensation in a form that explicitly converts

to equity when the firm gets into trouble and is bailout-proof.

Deferred stock

compensation, however, may do just the opposite. As long as there are

implicit government guarantees for financial institutions that are

considered too big, too complex or too interconnected to fail, the value

of those institutions' stocks increases with risk-taking.

The more risk a bank

takes, the greater the value of government guarantees and potential

bailouts. This value gets passed on to the bank's stock price. If

employees are paid in deferred stock, the risk incentives are then

passed on to them, encouraging them to speculate.

Rules that mandate more pay in the form of stock miss the point. It helps align the interests of employees and shareholders, but it fails to align their interests with those of taxpayers.

Ultimately, it's the

taxpayers who are held hostage. They care about the size of bailout

necessitated by excessive risk-taking taken by banks, and about economic

growth, but not about how bank profits are divided per se, since they

don't get a cut in any case.

Regulators are aware

that bank stockholders have an overriding desire to take more risk than

is good for society because chronic under-pricing of government

guarantees makes it profitable for banks to seek risky assets and lever

them as much as possible. This is the reason for capital requirements

and the Volcker Rule, which tries to restrict risk-taking.

Recent attempts to

reform compensation overlook how complicated the compensation process

can be. Trying to discourage risky behavior is like fighting an uphill

battle against shareholders who like risk. Moreover, risk incentives are

harder to measure, and their regulation is easy to circumvent.

Criticizing the

compensation packages of JPMorgan's Dimon and his senior associates

might be popular with voters, but regulators would be better off

focusing on the source of the problem -- the mispricing of government

guarantees that create perverse risk incentives in the first place.

Pricing deposit

insurance differently or banning activities such as proprietary trading

would give shareholders and employees alike an incentive to rein in

risk-taking. Employee compensation would then reform itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment